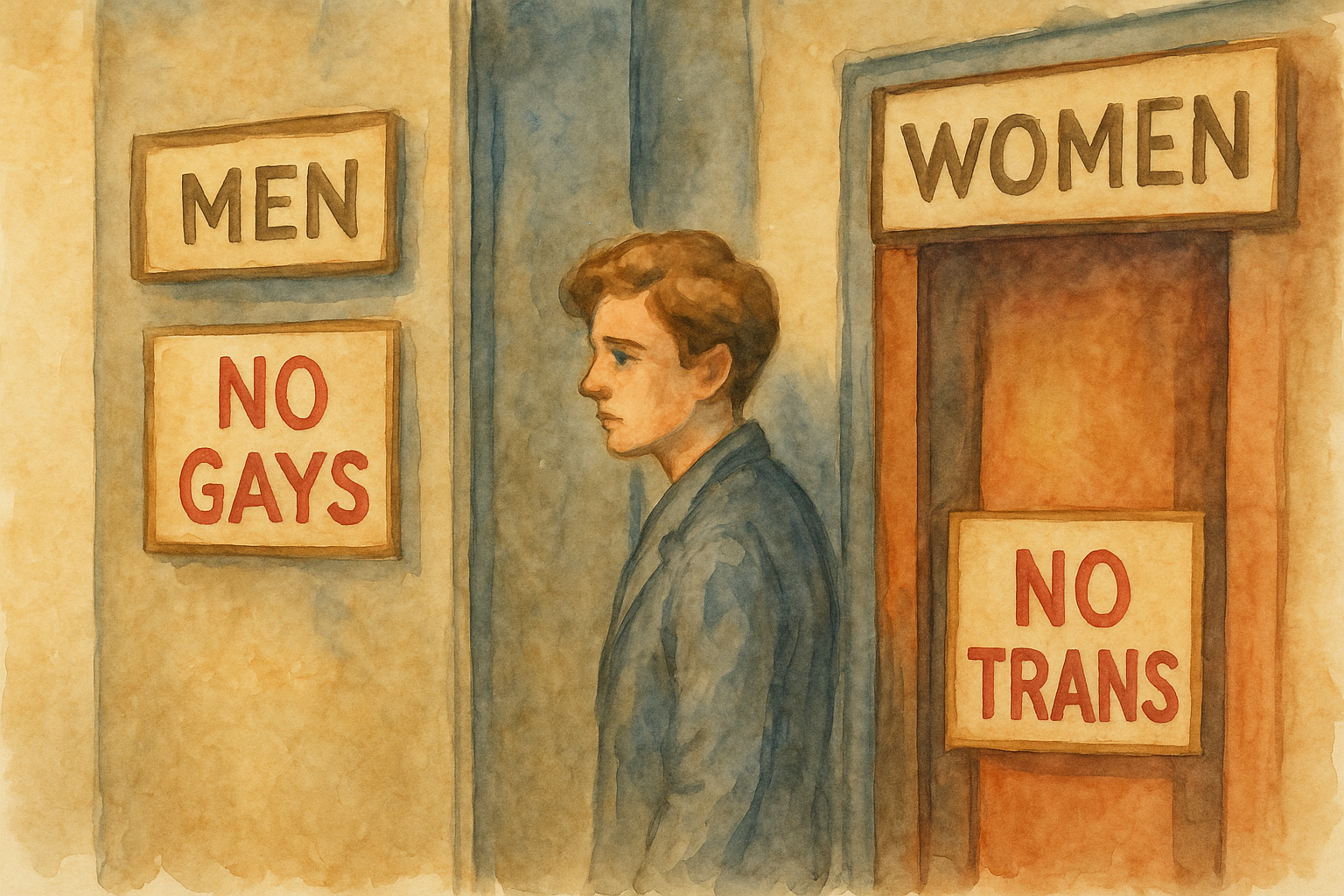

As June is Pride month, I have decided to have a look at something that has become a focus in recent weeks. Toilets and changing rooms are more than just practical spaces — they are social battlegrounds. Since the 1800s, these facilities have been used to enforce rigid gender binaries and moral norms, excluding both trans and gay people from public life. This exclusion is not incidental: it reflects how society polices bodies that deviate from heterosexual and cisgender expectations. This article explores the historical and contemporary significance of these exclusions, highlighting the shared experiences of marginalisation and resistance.

Victorian Infrastructure and Moral Panic

The 19th century marked the rise of urban planning, and with it came the gendering of public space. In Victorian Britain, public toilets were built primarily for men — supporting male participation in the public sphere. By contrast, women’s access was severely limited, based on the belief that respectable women should remain at home. Where women’s lavatories did exist, they were scarce, hidden, and carefully regulated.

This spatial segregation wasn’t merely about practicality. It reinforced Victorian ideals of purity, respectability, and the separation of public and private life. Transgressing these spatial rules — whether by gender presentation or sexual behaviour — attracted scrutiny and punishment.

Gay Men and the Criminalisation of Public Toilets

From the late 19th century, gay and bisexual men in the UK and US were frequently arrested for using public toilets, particularly under laws like the 1885 Labouchère Amendment, which criminalised “gross indecency” between men. Public lavatories became heavily policed spaces associated with illicit sexual activity — a perception that fuelled surveillance and criminalisation.

In the mid–20th century, police regularly used entrapment tactics to arrest men in cruising areas. The social stigma of being caught — often resulting in job loss, familial rejection, or imprisonment — terrorised a generation of queer men. These crackdowns embedded the idea that gay presence in toilets was both illegal and dangerous, shaping hostile public perceptions that persist today.

Trans People and Gendered Space

Trans people, especially trans women, have long been targeted for using gendered facilities. Laws and policing practices in the 20th century frequently punished people for “cross-dressing” or for occupying a toilet that didn’t match the gender assigned to them at birth. The consequences ranged from harassment and arrest to physical assault.

Importantly, nonbinary and gender-nonconforming individuals — including butch lesbians, femme gay men, and drag performers — have also experienced exclusion and violence. Their visibility often made them targets in spaces policed by rigid gender norms. The core issue wasn’t always sexual orientation or gender identity in isolation, but visible nonconformity.

Continuities in Contemporary Transphobia

Today’s debates over “single-sex spaces” in the UK and “bathroom bills” in the US echo these older moral panics. Opponents of trans inclusion often recycle 19th-century tropes: fears of deception, threats to women, and the sanctity of the binary.

However, evidence overwhelmingly shows that trans people are far more likely to be harassed than to harass anyone else in public toilets or changing rooms (Herman, 2013). Yet the exclusion persists — not because of risk, but because of deeply embedded ideas about who belongs and who doesn’t.

Shared Struggles, Shared Resistance

This history shows that both trans and gay people have been regulated and excluded from public spaces in ways that reinforce binary norms and control visibility. Toilets and changing rooms have been flashpoints — where inclusion is contested, and identity policed.

Recognising this shared history helps us understand why solidarity matters. Whether it was gay men surveilled in toilets, or trans women denied access to safe facilities, the mechanisms of exclusion have often been the same: suspicion, moral panic, and a fear of gender ambiguity.

Conclusion

For over two centuries, toilets and changing rooms have been more than sites of bodily necessity — they have been markers of social boundaries. Policing these spaces has meant policing queer existence.

Understanding this legacy reminds us that debates about access are not about convenience or comfort — they are about dignity, safety, and the right to occupy public space. For LGBTQ+ people, especially the most marginalised, the fight for inclusive bathrooms is part of the larger struggle for liberation. Contending with this deliberate social exclusion can, for many LGBTQ+ people, lead to feelings of shame and can be traumatising.

References

- Cavanagh, S. L. (2010). Queering Bathrooms: Gender, Sexuality, and the Hygienic Imagination. University of Toronto Press.

- Herman, J. L. (2013). Gendered Restrooms and Minority Stress: The Public Regulation of Gender and its Impact on Transgender People’s Lives. Journal of Public Management & Social Policy, 19(1), 65–80.

- Penner, B. (2013). Bathroom. Reaktion Books.

- Case, M. A. (2010). “Why Not Abolish the Laws of Urinary Segregation?” in Molotch, H. & Noren, L. (eds.), Toilet: Public Restrooms and the Politics of Sharing. NYU Press.

- Weeks, J. (2007). The World We Have Won: The Remaking of Erotic and Intimate Life. Routledge.